Protein is one of the three primary macronutrients, along with carbohydrates and fat. Proteins are required by the human body in relatively large quantities to maintain physiological homeostasis. From a biochemical perspective, proteins are complex macromolecules composed of amino acids that serve as the structural framework for cells and the functional machinery for metabolic processes. Unlike other macronutrients, the body maintains no specialized storage depot for protein. This means that consistent dietary intake is necessary to support continuous tissue turnover and systemic function.

The amino acid profile and dietary quality

The nutritional value of a protein source is determined by its amino acid composition. There are 20 standard amino acids used in the synthesis of human proteins. Nine of these are classified as essential amino acids (EAAs) because the body lacks the metabolic pathways to synthesize them de novo. For this reason, EAAs must be obtained through the diet.

Protein sources are categorized based on their "completeness." Complete protein are typically derived from animal products such as poultry, fish, and dairy, contain all nine essential amino acids in proportions that align with human requirements. Many plant-based sources are considered incomeplete because they are often deficient in one or more of the EAAs. However, consuming a diverse range of plant proteins, such as combining legumes with grains, can provide an efficient amino acid profile that is sufficient for good health.

Metabolic functions and energy contribution

Although the primary role of dietary protein is to provide the building blocks for growth and repair, it also plays an important role in energy metabolism. Each gram of protein provides approximately 4 kilocalories of energy. During periods of caloric restriction or exhaustive exercise, the body may convert amino acids into glucose through a process known as gluconeogenesis to maintain blood sugar levels. This is because, during caloric restriction, the body uses metabolic safeguards to ensure blood glucose levels remain within a narrow, physiological range. When dietary carbohydrate intake is low, the liver initiates the synthesis of glucose from non-carbohydrate precursors, such as protein.

If an individual is in a caloric deficit and does not consume enough protein, the body does not simply stop requiring glucose. Instead, it will mobilize amino acids from the body's largest reservoir: skeletal muscle. By increasing dietary protein intake during a "cut," you provide the liver with the necessary raw materials to produce glucose through gluconeogenesis without having to dismantle your own muscle tissue to do so.

The importance of adequate protein intake

When you decide to reduce your calorie intake to lose body fat, your body faces a significant challenge: finding enough energy to function correctly. When energy from carbohydrates and fats is insufficient, the body may mobilize amino acids from our muscles. Consuming enough protein provides a steady supply of amino acids, signaling to the body to prioritize fat oxidation while sparing existing muscle tissue. Higher protein intakes (often exceeding the standard Recommended Daily Allowance, or RDA) are necessary to maintain a positive nitrogen balance, especially when total caloric intake is low.

Nitrogen balance measures the adequacy of protein intake by comparing the amount of nitrogen consumed (primarily from dietary protein) to the amount excreted through metabolic wastes. A positive nitrogen balance means you are in an "anabolic" or building state, where you have enough protein for repair and growth. On the other hand, a negative nitrogen balance means you are in a "catabolic" state, where your body is losing more protein than it is getting by "eating" its own muscle for energy. Metabolism. Consuming protein at levels higher than the standard Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) is therefore essential to provide us with a surplus of nitrogen, which helps protect skeletal muscle despite being in an energy deficit.

Aim for above the minimum

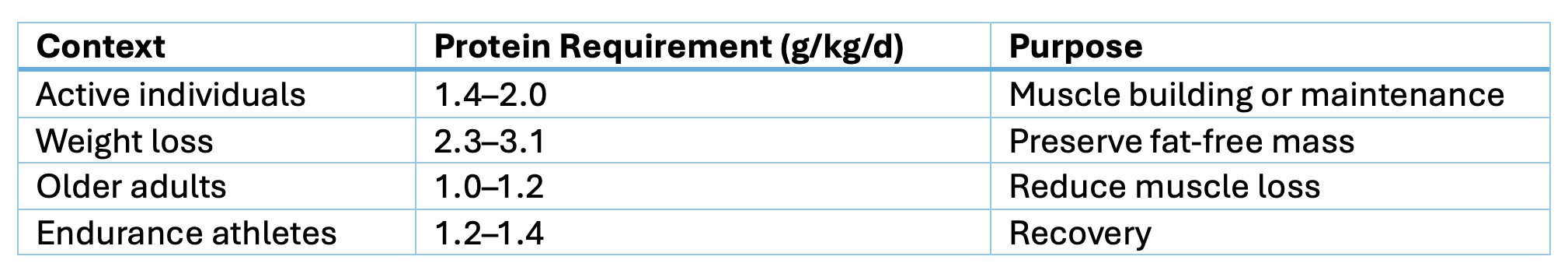

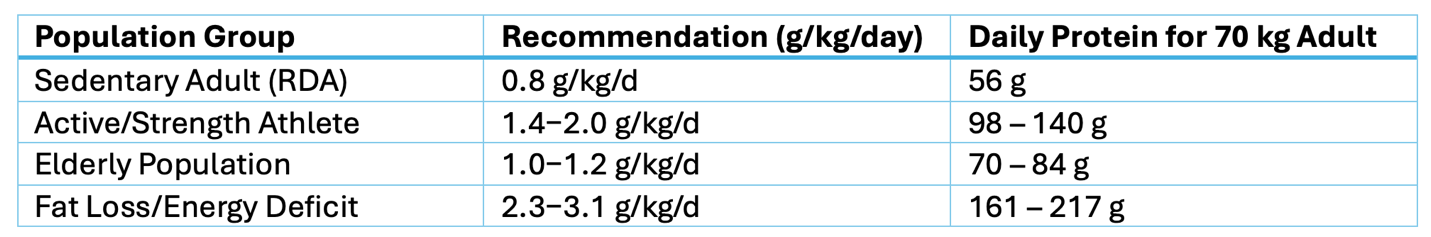

Protein intake should be adjusted based on age, activity level, and body goals. The Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA) for protein is 0.8 g/kg/day for healthy, sedentary adults aged 19 and older (1). While this amount is enough to prevent a basic deficiency in a sedentary person, it is often not enough for anyone who is active or trying to lose fat without losing muscle. The current guidelines recommend a daily intake of approximately 1.6–2.2 g/kg to support muscle growth and lean mass gains (2). Individuals who are in a caloric deficit should aim for 2.3–3.1 g/kg/day. Adjusting your intake to higher levels provides the nitrogen surplus needed to keep your muscles strong and your recovery on track, even when your total calorie intake is low.

Here's how these recommendations apply to a 70kg (154lb) person:

Nutrient Timing and the Anabolic Window

The idea of nutrient timing has long been a staple of gym culture, but modern science shows that the rules are much more flexible than we once believed (3). For years, the "anabolic window" was described as a frantic race to consume protein within thirty minutes of finishing a workout. However, the urgency to eat immediately after your session depends mainly on when you last had a meal; if you consumed a protein-rich meal within five hours of finishing your workout, your body still has a steady supply of amino acids circulating in your bloodstream, making post-workout shakes much less of an immediate requirement. Ultimately, reaching your total daily protein goal is far more important for muscle growth than the exact minute you eat your meals. While scheduling meals around your training can be a helpful habit to help you hit your targets, it should be viewed as a practical tool for consistency rather than a strict physiological necessity.

Tailoring protein intake for strength and endurance athletes

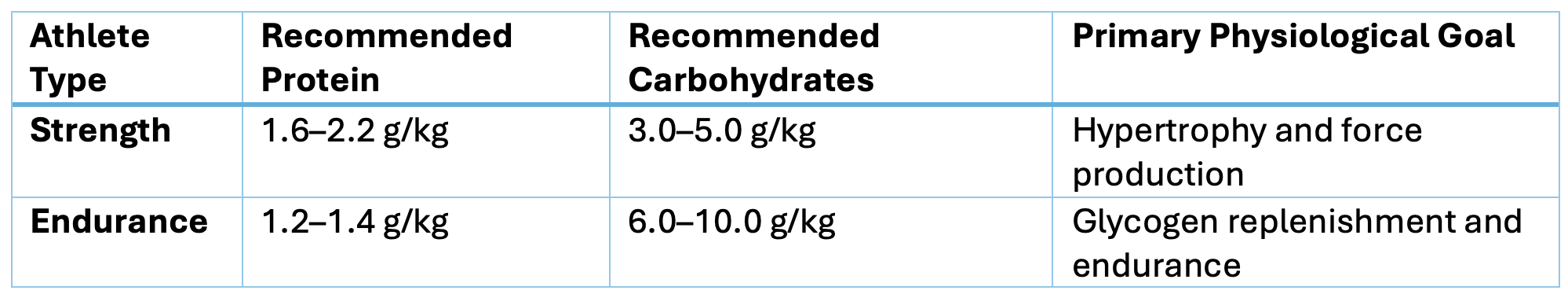

For maximal performance and body composition, athletes should adjust their macronutrient distribution to align with the metabolic demands of their specific training. Strength athletes generally require a higher protein-to-carbohydrate ratio to maximize muscle protein synthesis and recovery from high-intensity resistance training. In comparison, endurance athletes should prioritize a higher carbohydrate-to-protein ratio to maintain glycogen stores.

For strength athletes, the emphasis is placed on creating an anabolic environment. Because weightlifting causes significant micro-trauma to muscle fibers, providing a surplus of amino acids is essential for repairing and rebuilding those tissues. While carbohydrates are still necessary to fuel training sessions and support recovery, they play a secondary role to protein in the context of structural adaptation.

For endurance athletes, the nutritional priority shifts toward energy availability. During long bouts of exercise, the body relies heavily on muscle and liver glycogen; if these stores are depleted, performance declines sharply. This is a phenomenon we often describe as "hitting a wall." While protein intake is lower compared to strength athletes, it is still necessary to support the repair and to provide substrates for gluconeogenesis during the latter stages of an event. Maintaining these ratios enables endurance athletes to recover without compromising the energy density necessary for their sport.

Animal vs. Plant-Based Proteins

Animal proteins and plant-based proteins differ in their ability to stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS). A single serving of animal protein is approximately 20 to 25 grams, which tends to spark a more robust muscle-building response than an equal amount of plant protein. This is primarily attributed to the higher density of essential amino acids (EAAs), particularly leucine, found in animal-derived sources like meat, dairy, and eggs.

Plant proteins are often considered "incomplete" because they lack enough EAAs required for optimal repair and growth. For example, cereal grains are often low in lysine, while legumes like beans and lentils may be deficient in methionine. If these proteins are consumed in isolation, their ability to support muscle maintenance may be compromised compared to their animal-based counterparts.

However, athletes and health-conscious individuals following a plant-based diet can still achieve identical results by diversifying protein sources. Combining grains and legumes throughout the day allows you to create a complete amino acid profile. Additionally, because plant proteins are sometimes less digestible due to their fiber content, slightly increasing your total daily protein intake can help compensate for these minor deficiencies.

Fast vs. Slow Proteins: Whey and Casein

Whey Protein is often referred to as a "fast" protein due to its rapid rate of digestion and absorption. When consumed, whey protein leads to a sharp and significant increase in blood amino acid levels within approximately 60 to 90 minutes. The rapid delivery of amino acids, particularly their high leucine content, enables whey to efficiently and immediately stimulate muscle protein synthesis (MPS). For these reasons, whey protein is considered especially beneficial when taken after exercise, during the post-workout period, when the body is most receptive to nutrients that promote muscle repair and growth.

Casein Protein, by contrast, is classified as a "slow" protein. Upon ingestion, casein coagulates in the stomach, which slows its digestion and results in a gradual, sustained release of amino acids into the bloodstream over several hours. This prolonged release makes casein particularly valuable for preventing muscle protein breakdown during extended periods without food, such as overnight sleep, supporting muscle maintenance and recovery.

Performance Impact studies indicate that although whey protein is more effective for acute increases in muscle protein synthesis immediately after exercise, both whey and casein proteins lead to similar improvements in muscle mass and strength over time when total daily protein intake is consistent. Therefore, incorporating either or both types of protein can help support muscle growth and athletic performance if overall protein needs are met.

An important note about BCAAs

For a long time, branched-chain amino acids BCAAs were heavily marketed and a popular supplement among the fitness community. BCAAs are a group of three essential nutrients: leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Among them, leucine is by far the most significant because it acts as a molecular "on-switch" for the mTOR pathway, the primary system the body uses to signal muscle growth and repair. Without enough leucine, the body simply won't initiate the process of building new tissue (4).

However, while leucine starts the process, it cannot finish it alone. Think of leucine as the spark that starts an engine; you still need fuel, but you still need the other essential amino acids to keep the car moving. Supplementing with BCAAs is generally unnecessary if you are already consuming enough total daily protein from whole food sources. Adding extra BCAAs provides no additional benefit and is often an inefficient use of your nutritional budget.

Summary

- Prioritize Total Intake: Aim for a daily protein intake between 1.4 and 2.0 g/kg/day to build and maintain muscle mass.

- Focus on Quality: Choose high-quality, whole-food proteins, such as dairy, eggs, and lean meats, as these are rich in essential amino acids and leucine, the primary trigger for muscle growth.

- Flexible Timing: While eating near your workout is beneficial, the "anabolic window" lasts at least 24 hours. Meeting your total daily goals is more important than the exact minute you consume a post-workout shake.

- Enhanced Fat Loss: When in a calorie deficit, increasing protein to 2.3–3.1 g/kg/day helps maximize fat loss while protecting your hard-earned muscle.

- Nighttime Recovery: Consuming 30–40 g of casein protein before sleep may improve overnight recovery and boost your metabolic rate the following morning.

- BCAAs Intake: Supplementing with BCAAs will not provide any additional benefit if you are consuming enough protein throughout the day.

References

1) National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. (n.d.). Nutrient recommendations: Dietary Reference Intakes (DRI). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://ods.od.nih.gov/HealthInformation/nutrientrecommendations.aspx

2) Jäger R, Kerksick CM, Campbell BI, Cribb PJ, Wells SD, Skwiat TM, Purpura M, Ziegenfuss TN, Ferrando AA, Arent SM, Smith-Ryan AE, Stout JR, Arciero PJ, Ormsbee MJ, Taylor LW, Wilborn CD, Kalman DS, Kreider RB, Willoughby DS, Hoffman JR, Krzykowski JL, Antonio J. International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand: protein and exercise. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2017 Jun 20;14:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0177-8

3) Casuso, R. A., & Goossens, L. (2025). Does Protein Ingestion Timing Affect Exercise-Induced Adaptations? A Systematic Review with Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 17(13), 2070. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17132070

4) Kaspy, M. S., Hannaian, S. J., Bell, Z. W., & Churchward-Venne, T. A. (2024). The effects of branched-chain amino acids on muscle protein synthesis, muscle protein breakdown, and associated molecular signalling responses in humans: An update. Nutrition Research Reviews, 37(2), 273-286.http://doi.org/10.1017/S0954422423000197